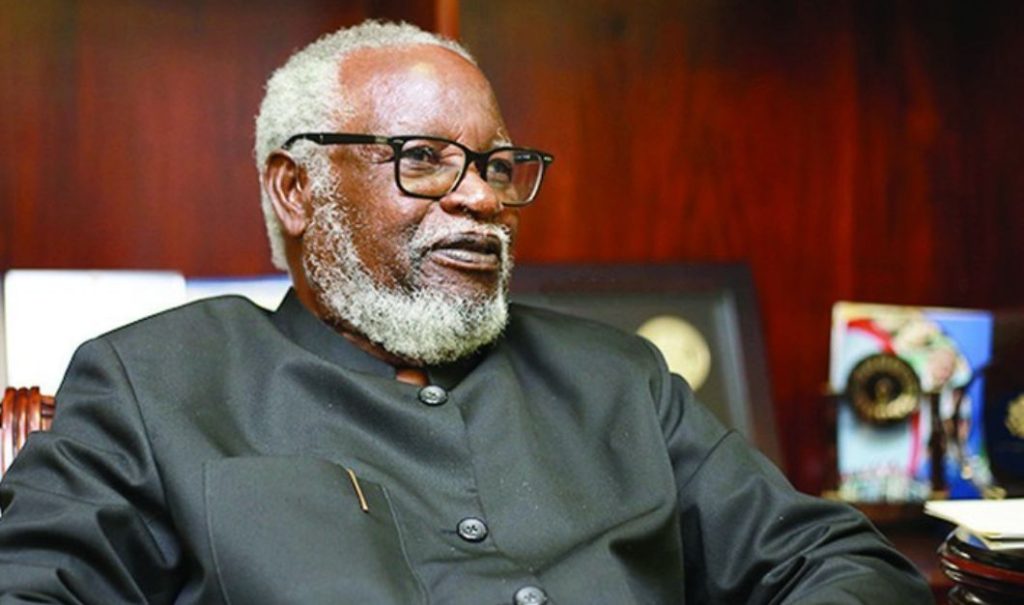

The passing of Sam Nujoma on 8 February 2025 presents a fitting moment to assess the contribution and legacy of Namibia’s founding president.

1. Lightning strikes multiple times

The combat name he chose for himself was ‘shafiishuna’ which according to his own interpretation meant ‘lightning’ (others have alternative understandings see note at the end of the article). The name reflects the dynamism which propelled his tireless campaigning for independence. From 1960 he managed, with a small group of supporters, to put the cause of Namibian independence on the international agenda within a decade and build the reputation of his movement to the point when in the mid-1970s the UN recognised Swapo as the ‘sole and authentic’ representative of the Namibian people. During that period he was hardly ever in the same place – always lobbying, negotiating and representing.

2. No blind alleys

His political outlook was rooted in African nationalism rather than strictly socialist or capitalist approaches. This enabled a very necessary flexibility, allowing Swapo to operate on both sides of the Cold War – gaining military and other aid from the Soviet Union and the eastern bloc and material aid and educational support from Scandinavia and the other Western nations. His political outlook, particularly his scepticism about Communism, enabled the Namibian government to adopt a pragmatic approach to policymaking after 1990 – rather than ending up in an ideological cul-de-sac.

3. Removing the tribal blinkers

Although he started his political career as the leader of the Ovamboland People’s Organisation, he quickly realised the need for an inclusive, nationalist liberation movement. Hence he sought to ensure Swapo was representative of Namibia as a whole – reaching out to leaders like Hendrik Witbooi in the south, among others. This wasn’t always easy or risk-free. He brought in Caprivians – which ultimately resulted in Mishake Muyongo becoming vice-president of Swapo (he eventually led a separatist rebellion in the late 1990s). Later tribalism and anti-intellectualism fuelled the detainees saga of the 1980s – a tragic episode that Nujoma seems to have been unable to control or limit. However, the ‘one Namibia, one nation’ approach enabled Nujoma to create a multi-racial, multi-ethnic first Cabinet in 1990 that was able to placate fears and build confidence.

4. Knowing his limits

His decision to seek a third term can still be criticised for stymying democratic progress within his party and the country. However, at least he stopped there. Despite rumours to the contrary, he never seriously considered a fourth term. In the context of what has happened in sub-Saharan Africa since, with leaders from Rwanda to Congo (Brazzaville) making a mockery of their constitutions, his decision to stick to three terms in office remains an example of the necessity for constitutional order and the importance of allowing political transitions to take place.

5. Resisting the temptation

His decision not to endorse any candidate before the 2012 special congress, which chose a new Swapo presidential candidate, allowed a genuine democratic contest to take place. He even avoided backing his son for a position in the Swapo executive. He most likely held strong private views about the succession process but was admirably restrained in public to the surprise of many. This ensured that no one could be accused of being pushed into the presidential candidate role on a Nujoma bandwagon.

6. Not your average kleptomaniac

For the most part he rejected luxurious living – opting for an abstemious lifestyle based on a healthy diet and exercise. In an era when many of his generation of African leaders were highly corrupt kleptomaniacs, his approach was exemplary. On his retirement he did not receive a grand mansion but instead opted to live either at his private farm near Otavi and at a Swapo-owned property just outside Windhoek. Only ten years after his retirement did the State decide to build him an official home.

7. Learning from the school of hard knocks

Although some have taunted him for his lack of education – this was obviously a consequence of the apartheid system that denied quality schooling and university opportunities to the majority of the population. Despite the fact that his only formal qualification was a Standard Six certificate he went on to achieve much more than most of his more ‘educated’ contemporaries. His belief in lifelong learning was underlined when he enrolled for a master’s degree in geology after his retirement from politics. His life has demonstrated that formal educational achievements are not a prerequisite for success in life as business personalities like Bill Gates and Richard Branson can testify.

8. Down with the people

According to those close to him, he has never seen himself as above his fellow comrades. Hence, he was quite happy to complete ordinary duties in the exile camps and take a hands-on lead in post-independence projects like the Tsumeb-Oshikango railway which he urged citizens to help with on a voluntary basis. His willingness to get his hands dirty in the cause of development has broadened his appeal among ordinary people.

9. Moving on

Despite predictions that he would remote control his predecessors, there’s very little evidence that this happened. Instead, he retired from active, day-to-day politics and only appeared on a party-political stage when requested to do so by Swapo. No doubt the temptation must have been strong to intervene directly at times. After his three terms in office, he remained mostly in the background.

10. A life well lived

It’s hard to think of an individual who has more greatly influenced the formation of a nation but then had the good sense to get out of the way and let the country find its own feet. Nelson Mandela? But he was already 80 years old when he stood down (Nujoma was 74 when he left office in 2005). Others like Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe sullied their own early liberation credentials with their latter-day authoritarianism. The closest comparison may be George Washington – who for many remains the most exemplary of America’s early leaders. Like almost all politicians who have been in long-term leadership positions there are less-distinguished periods, intemperate and unwise words and actions, and mistakes which had varying consequences. But taking his five decades of political activity as whole, Nujoma emerges with more credit than most historical leaders – for what he did at crucial junctures but also for what he didn’t do – which sets him apart from many of the short-lived icons of the liberation era.

*Note: The interpretation of the word ‘Shafiishuna” as lightning is based on Sam Nujoma’s own understanding of his name as relayed to journalist Baffour Ankomah in New African magazine in 2003. The exchange was as follows:

Baffour: Your middle name, Shafiishuna, what does it mean?

Nujoma: That is my combat name. Shafiishuna means lightning. Eshuna means a terrible thing like lightning. During the struggle, each of our guerrillas had a combat name.

Baffour: So why did you choose that name, Shafiishuna?

Nujoma: Because it was in my family, on my father’s side.

The author Graham Hopwood is the Executive Director of the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR)